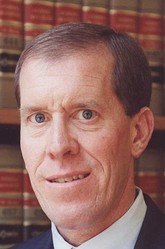

General Bio

William H. Pauley III, United States District Court federal judge of the Southern District of New York, has a reputation for austerity and sober directness as he presides over the court. Presiding over one of the most important district courts in the country, which has jurisdiction over important New York City businesses, such a mien is entirely appropriate, and makes him a good fit for the job.

Pauley was born in Glen Cove, New York. He received his A.B. from Duke University in 1974, and his J.D. from Duke University School of Law in 1977. With Duke as one of the "T-14" law schools, consistently ranked in the top 14 in the U.S. News & World Report's annual rankings, it gave him the sort of background we would expect from a federal judge - a strong and solid basis for building his career in federal law. The school has been ranked 8th best law school in 2011 by law firm recruiters.

Certainly it helped land him as a law clerk in the Office of Nassau County Attorney, New York, which he commenced immediately after graduating. Keeping busy in his initial years on the market, he also went into private practice in New York City from 1978 to 1998, and worked as Assistant Counsel, New York State Assembly Minority Leader, in New York from 1984 to 1998. In private practice he worked in a Manhattan law firm focusing on complex federal civil litigation, fitting preparation for where he was heading.

Pauley was nominated on May 21, 1998, by President William J. Clinton, on the recommendation of U.S. Senator Daniel Patrick Moynhian, to fill the seat vacated by Peter K. Leisure. He was confirmed by the Senate on October 21, 1998 on a Senate voice vote, and received the commission the next day, filling seat #23.

He is also a member of the Federal Bar Council, the Association of the Bar of the City of New York, and the Nassau County Bar Association.

Personality

As befits a man of his prestige and placement, Pauley has been called stern and forceful in addressing advocates. Many sloppy lawyers have grumbled after he took them to task, as he is not one to suffer fools, but sharply reprimands and interrogate those who would give slipshod answers to his questions. The demeanor of his court is sober, though augmented by his dry sense of humor and ironical wit.

"A courtroom is a formal place," he said, "Serious things happen here. This is my view as a lawyer and a judge."

Attorneys who have weathered his court often are struck by the austerity his presence commands, though some grumble that his judgments against a lawyer's competence are stark, visible, and permanent. He might have a mild sense of humor, but he never masks his intolerance for ineptitude.

With such a formidable court presence, some may wonder if Pauley has a tender personal side. Of course he does. A lawyer who worked with him at a law firm, Franklyn Snitow, observed that "He was so much of a lawyer and such a hard worker that when he did relax it was out of character."

One moment that the judge's sensitive side did come out happened when he saw an associate at his firm faint. Though she recovered, the judge wept. "He is a stern person, but that revealed an aspect of his soul that might not have been apparent," said Snitow.

Pauley, the father of three boys says, "I live the life of anyone in the suburbs, which is shepherding my children and other people's children to and fro."

He enjoys sports, and follows with interest Duke's basketball team.

Specific Cases

Ben-ami Kadish

One of Judge Pauley's first exposures to the world as federal judge concerned the case of Ben-Ami Kadish, a former U.S. Army mechanical engineer who pled guilty in December of 2008 for working as an "unregistered against of Israel" and giving classified U.S. documents to Israel in the 1980's. Kadish worked as an Israeli government agent from 1979 to 1985, disclosing information of American nuclear weapons, Patriot missiles, and so forth.

Pauley said with a hint of exasperation, "This offense is a grave one that implicates the national security of the United States. Why it took the government 23 years to charge Mr. Kadish is shrouded in mystery." He further noted that prison would "serve no purpose" for a man as old as Kadish, and chose instead to fine him for $50,000.

Certainly this proved less severe than the talk surrounding Kadish's treachery, which had even suggested the death penalty. The judge nevertheless proved dissatisfied with the entire case, noting that "It's clear that the government could have charged Mr. Kadish with far more serious crimes." His ultimate verdict appears to have fallen on the FBI and the U.S. Government.

Monserrate

Judge Pauley's decision in the case of Monserrate v. NEW YORK STATE SENATE simply dismissed Monserrate's request to balk the Senate's decision against him. Former New York State Senator Hiram Monserrate was reacting to the New York Senate decision to expel him on February 9, 2010, after he was convicted of domestic violence against his girlfriend, a misdemeanor charge.

"The question of who should represent the 13th Senatorial District is one for the voters, not this court," said the judge, summarily, in his 25-page decision.

Though Monserrate appealed the decision to the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, they ruled against his appeal.

Dot-Com Collusion

Perhaps the first big case to give Pauley renown regarded his ruling on March 18, 2010against disbanding regulating collusion between investment bankers and analysts at Wall Street firms. The case involved big business, with the largest firms on Wall Street. Those firms hoped to change regulation established in 2003, and for the most part the judge agreed with the changes they hoped to make, excepting their attempt to legalize unsupervised interactions between investment bankers and analysts.

Pauley insisted that the separation between independent analysts and bankers must remain in place to increase confidence in the market. Though some of the modifications placed after the dot-com bubble burst were to be dismissed, after being submitted to Pauley for approval, he strongly disagreed with dismissing this last one.

"Such a proposed amendment is counterintuitive and would undermine the separation between research and investment banking," said Pauley. "The parties' proposed modifications would deconstruct the firewall between research analysts and investment bankers."

Thus that proviso was held in place, that investment bankers and analysts cannot discuss transactions without a compliance official present.

Unpaid Internships

Judge Pauley's decision in the case regarding unpaid internships in July of 2013 surprised many and gave them the anticipation that the logic and precedent of his ruling might spread beyond his jurisdiction.

The case pertained to unpaid interns. Throughout the country, internship has traditionally been viewed as a rite of passage. Fresh candidates, usually in college or recently graduated, can garnish their résumés with the credits of having worked, gaining experience and connections, and in return they will have done so free.

The case of Glatt v. Fox Searchlight Pictures broke the tradition, saying that not paying interns violates the Fair Labor Standards Act.

The case revolved specifically around two interns working on film production crews, one of them Black Swan, the Academy Award winning film starring Natalie Portman.

The internship programs benefit employers, who get free labor, and sometimes benefit employees, who get props on their résumés, but cost workers who normally would be paid to do what the interns are doing. In this case, the intern on Black Swan did the sort of work the studio would normally have to pay for, such as grabbing lunches, running errands, and doing monkey work.

Though the interns know what they are getting into, the Fair Labor Standards Act "Does not allow employees to waive their entitlement to wages," the judge explained.

The new standard of interns imposed by the court sets that interns should be considered trainees, getting valuable education, and not doing work the employers would otherwise be paying for. As the judge explained, the unpaid internships should not be to the immediate advantage of the employer.

Pauley rejected the "primary benefit test," which determines whether "the internship's benefits to the intern outweigh the benefits to the engaging entity," calling it subjective and unreliable. Instead he claimed that the intern must receive vocational training and not uproot regular employees.

"Undoubtedly Mr. Glatt and Mr. Footman received some benefits from their internships, such as résumé listings, job references and an understanding of how a production office works," explained Judge Pauley. "But those benefits were incidental to working in the office like any other employees and were not the result of internships intentionally structured to benefit them."

"Searchlight received the benefits of their unpaid work, which otherwise would have required paid employees."

NYC Pregnancy Center Disclosure Law

Pauley blocked a law meant to go into effect July 13, 2011. The law meant to attack centers who offered advice to young women regarding their pregnancies. Abortion rights advocates claimed such centers deceitfully pretended they would give referrals for abortions when in fact they hoped to talk women out of the idea.

The agencies who fought the new law, which would require pregnancy centers to declare if they had licensed medical staff and would protect clients' privacy, argued that though they offered pregnancy tests, ultrasounds, and counseling, they did not offer referrals for abortions based on moral and religious reasons.

This the judge agreed with, that the law that would suppress such agencies appeared unconstitutionally vague. He noted that the law would "compel them to speak certain messages or face significant fines and/or closure of their facilities."

Since these organizations offered free services such as pregnancy tests, and since they did so to further religious beliefs, they should not be judged by the strictures of commercial speech. If they did, that "would represent a breathtaking expansion of the commercial speech doctrine."

He further repudiated the argument that these agencies did engage in commercial speech on the argument that they were spreading their beliefs as "particularly offensive to free speech principles," comparing such free speech to those who passed out flyers for political rallies, religious literature promoting church attendance, or similar forms of expression," which is not commercial speech.

NSA

Pauley made a controversial ruling in 2013 over the fiercely debated topic of NSA data collection. The issue, brought to national attention after Edward Snowden breached military trust and exposed top secret programs the government set in place after the 2001 attack on the World Trade Center, has sharply divided opinions.

The NSA had adapted a few controversial programs, one of which was the collection of metadata from phone use. With this program, authorized under the Patriot Act, a legislation set in place to empower the government to effectively answer the September 11, 2001 attack, the government agency was authorized to collect information on what numbers are being dialed, so-called "metadata" that telephones give whenever a number is dialed.

Though Richard Leon, judge over the United States District of Court for the District of Columbia, had ruled that the authorization for such a mandate was outdated, and was hence not lawful. Pauley disagreed.

The precedent they turned to was in Smith v. Maryland, and Pauley upheld the 1979 decision saying:

"In Smith v. Maryland, 442 U.S. 735 (1979), the Supreme Court held individuals have no 'legitimate expectations of privacy' regarding the telephone numbers they dial because they knowingly give that information to telephone companies when they dial a number. 442 U.S. at 742. Smith's bedrock holding is that an individual has no legitimate expectation of privacy in information provided to third parties."

Pauley was careful to explain that his decision regarded the constitutionality of the practice, not the merits on whether it should or should not continue.

"The natural tension between protecting the nation and preserving civil liberty is squarely presented by the Governments' bulk telephony metadata collection program. Edward Snowden's unauthorized disclosure of Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court ("FISC") orders has provoked a public debate and this litigation. While robust discussions are underway across the nation, in Congress, and at the White House, the question for this Court is whether the Government's bulk telephony metadata program is lawful. This Court finds it is. But the question of whether that program should be conducted is for the other coordinate branches of Government to decide."

Despite the tone of disinterest, or judicial distance from the merits of this program, Pauley nevertheless expressed his opinions on the matter that demonstrated his comfort and appreciation of the program.

The judge considers the program as useful in countering terrorism, and that it "only works because it collects everything."

He said it "represent the government's counter-punch" to al-Qaida's terror network's technological sabotage of American culture.

"The blunt tool only works because it collects everything. The collection is broad, but the scope of counter terrorism investigations is unprecedented."

Clearly the judge viewed the 9-11 attacks with the soberest concern, saying they "revealed, in starkest terms, just how dangerous and interconnected the world is. While Americans depended on technology for the conveniences of modernity, al-Qaida plotted in a seventh-century milieu to use that technology against us. It was a bold jujitsu. And it succeeded because conventional intelligence gathering could not detect diffuse filaments connecting al-Qaida."

"The government learned from its mistake and adapted to confront a new enemy: a terror network capable of orchestrating attacks across the world. It launched a number of counter-measures, including a bulk telephony metadata collection program - a wide net that could find and isolate gossamer contacts among suspected terrorists in an ocean of seemingly disconnected data."

Despite his appreciation for the program, Pauley softened his words by considering the other side of the issue, saying the program had the potential to "imperil the civil liberties of every citizen," and encouraged the nation to debate the subject.

He nevertheless repudiated the ACLU's claims that the program lent itself to such mischief as exposing when a person called a suicide hotline. He claimed the NSA cannot query the database without legal justification, and said "the government repudiates any notion that it conducts the type of data mining the ACLU warns about in its parade of horribles."

The wide-reaching nature of the telephony program was necessary, he explained, in repudiation of the ACLU's argument that the collecting was too wide: "The argument has no traction here. Because without all the data points, the government cannot be certain it connected the pertinent ones. Here there is no way for the government to know which particle of telephony metadata will lead to useful counter terrorism information. When that is the case, courts routinely authorize large-scale collections of information, even if most of it will not directly bear on investigation."

Those perusing this case, which Pauley had dismissed, appealed the ruling at the Second District Court, which is often the next stop for litigation that has passed the District Court for the Southern District of New York.

Image credit: Wall Street Journal